Do Plant Hardiness Zones Matter with Dan McKenney and John Pedlar

Download MP3[00:00:00] Introduction to Plant Hardiness Zones

Susan Poizner: In the old days, if you wanted to buy and plant a fruit tree, there were a few things you needed to consider, and a big one was what plant hardiness zone you lived in. And that's because not all trees will survive in all climates. Here in Toronto, Canada, we can easily grow a wide range of fruiting trees, including apples, cherries, pears, and plums.

But many other plants won't survive our cold winters. So plant hardiness zones are supposed to tell us which plants will thrive in our climates and which plants will not.

[00:00:38] Questioning the Plant Hardiness Zone System

Susan Poizner: But people are starting to question the plant hardiness zone system. Our climate is changing and there's a lot of extreme weather events today.

So the question is, are plant hardiness maps still useful? And that's what we're going to talk about in the show today.

[00:00:55] Meet the Experts: Dan McKenney and John Pedlar

Susan Poizner: I have two research scientists from Natural Resources Canada joining me to discuss this topic. They are Dan McKenney, PhD, and John Pedlar. Dan and John, welcome to the show today.

Dan McKenney and John Pedlar: Hi, Susan.

Thanks very much for the invite.

Susan Poizner: It's great to have you on the show.

[00:01:16] Understanding Plant Hardiness Zones

Susan Poizner: So now, tell me a little bit about plant hardiness zones. What are they, and how does the system work?

Dan McKenney: John, I'll have a go at it. I think, as you alluded to, Susan, it's like a generalized map that tries to give people an indication of what plants are suited for my area or your area, typically related to climatic conditions.

But a tricky thing with a single general map is that it's trying to force fit everything into one kind of legend or classification. But if you think about it like birds, unless you're a seagull, birds have their special habitat that they like, trees have their special habitat, they'll like, so we're trying to force fit these general preferences into one general useful map.

Susan Poizner: I like that comparison because nobody questions with birds that you know that there are certain birds that like tropical climates. And yet, with trees, we think we can go to the garden center, grab whatever we feel like, pop it in the ground, and that you just assume that it's going to work, but it really might not.

Dan McKenney: That's right. I think that, experience over time, has given people the benefit of knowing what can fit into particular zones. But I think what a lot of people don't realize is that there is not a lot of testing that goes on or that had gone on into what does fit into the zones. I don't know if you want to get into the Canadian zone right now, but the Canadian system was really based on the testing of just 174 plants.

Back in the early 1960s, and then they worked out what they worked out a statistical model that identified the suitability of the plants to in 108 locations across the country, and they came up with a nice formula that relates to seven different climate variables, and they basically had this statistical model. And then, at 640 weather stations, they hand drew lines on a map that basically indicated where those zones were.

So it was fairly straightforward. It works to a certain degree, but there's not been a lot of testing since then.

Susan Poizner: Okay, I'm going to back up here for a second. Did you say they tested 174 plants? There's more than that, even just in a local garden center, there's more than 174 plants.

What plants did they test, and then how do we know what other plants will fit where in the system? There seems to be a big hole there. Am I missing something?

John Pedlar: No, I think you're right there, Susan. There was quite a range of 174 species. Again, that was back in the 1960s that they were the original plants that they used to develop the zones in Canada.

That's not to say that there's been no testing since then. There are facilities, both in Canada and the United States, that devote a significant effort to testing plants, but I think it's generally agreed that there is a weakness with the broad range of plants that are available, as you've pointed out. There's certainly some that slip through the cracks and probably don't get as rigorous of hardiness testing as they should.

Susan Poizner: Okay, so guys have mentioned the Canadian system.

[00:04:49] The Canadian vs. American Systems

Susan Poizner: How does the Canadian system differ from the American system of plant hardiness zones?

Dan McKenney: The Canadian system is based on seven different climatic variables. We have a pretty harsh climate up in this part of the world, even in Toronto, Susan, at times.

So these variables were the mean minimum temperature of the coldest month, frost free period in days, rainfall from June through November, the maximum average temperature of the warmest months, rainfall in January. Really, rainfall in January is different in a place like Victoria, British Columbia, versus Chapleau, Ontario, where rain in January would be a pretty unusual occurrence, perhaps occurring a little more now.

The mean maximum snow depth. Snow protects plants in winter, and maximum wind gust in 30 years. Those were the variables that were used that created the best formula for the researchers from Agriculture Canada back in the 1960s when they did this work.

Susan Poizner: Okay. So in Canada, we have seven variables. Seven variables, including snowfall and wind and rain. We're keeping everything in mind.

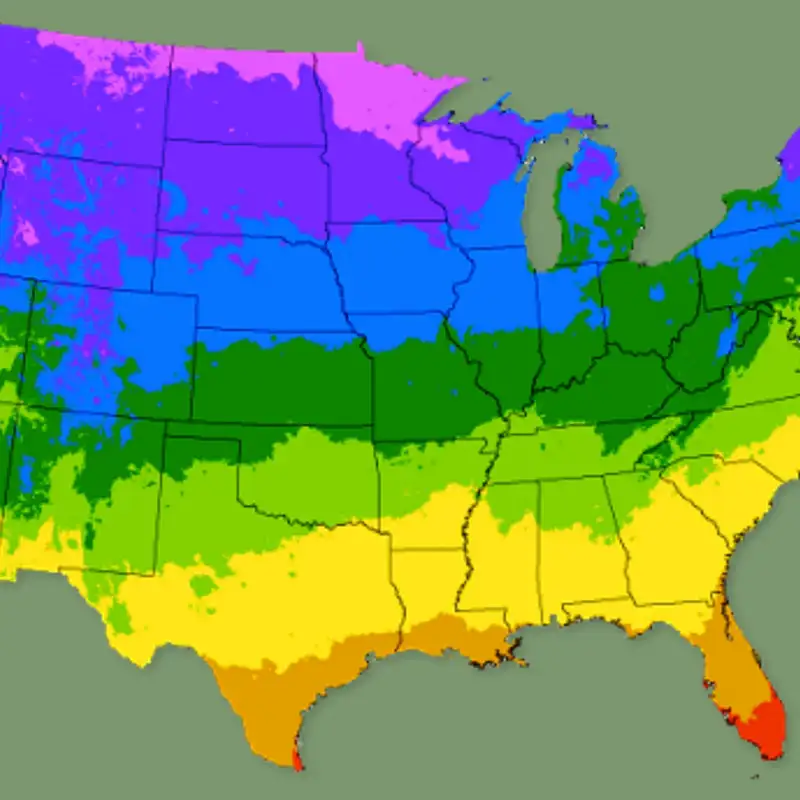

What about in the United States? They have a very beautiful plant hardiness zone map with lots of great colors. I love the map. It's very attractive. How many variables do they have in the United States?

John Pedlar: So in the United States, they've zoned right in on extreme annual minimum temperature.

So it's a single variable system in the United States and should note that that's actually the most widely used system in the world, as far as I know. It's used across North America, including Canada and in Europe as well. So it's done a good job and it's been widely uptaken by different regions.

It's just a bit of a different system though, clearly, than what was developed in Canada.

Susan Poizner: So here I am in Canada, and I want to buy a plant from the United States. Let's say I want to bring a fruit tree over, and I'm zone 5b. If I have different variables than the U.S. climate zone map, am I safe? Is there any kind of conversion I need to do?

Dan McKenney: Some of the work that we've done, we've basically mimicked the USDA, the United States Department of Agriculture's approach. We've got maps of extreme minimum temperature as well, so you can identify in Canada what the USDA zone is, for your part of the world. I think a lot of people think that. All you need to do is add one. The Canadian zone is one higher than the U.S. zone, but it's not actually the case. It's a lot more complicated because there's, call it spatial variation in the U.S. zonation, that doesn't mesh exactly with each zone. So zone 5a could be zone 4 in Canada. Could be zone 5 in Canada. In fact, we've even written a paper on how much variation there is across all these zones. In fact, the Canadian zones span eight or nine USDA zones, at times. Again, because of the fact that we have these other variables, it complicates things.

And snow is a big thing. It does protect plants.

[00:08:39] Impact of Mulching and Snow on Plant Hardiness

Susan Poizner: I want to talk about snow, what you just said, because we got a great email. It's from David from Lansing, Michigan. His question is, what are your thoughts on heavily mulching of a tree, like a fruit tree, to extend your hardiness zone?

You were talking about how snow insulates the roots of a tree and of plants. What about mulching with wood chips? Can that mean that a more tender tree can survive in a colder climate if you do that?

John Pedlar: Yeah, I've heard that as a method for helping to protect roots not, as you mentioned, unlike what snow would do for roots as well, so that could certainly help. There are other aspects to cold hardiness other than just protecting those roots, although that's important. There are other tissues that can be damaged either through early fall frosts or through late spring frosts.

Mulching can help, but it's not going to solve all your cold hardiness issues.

Susan Poizner: So what you're saying. Go ahead.

Dan McKenney: I was just going to add that one of the reasons why I think rainfall in Canada in January is an important variable is that roots don't like to get frozen. And because we have colder temperatures, rain in January, followed of course, by colder weather, can cause mortality to plants. It's problematic.

So in a place like Michigan, which is just south of where we are, John and I, yeah, I think anything you can do to protect plants. And if there are micro climates that exist near people's homes, because they may be in a hollow that might cause cold air pooling, but if they're near a house that might protect and basically be a a little bit more protective of plants that would be in the zone that you are, you might be lucky in that regard.

Susan Poizner: Yeah, there's room. There's wiggle room, and especially for creative people who might want to experiment, I think that's a really interesting point. Let me see. We got a couple more interesting emails.

[00:11:02] Listener Questions and Expert Insights

Susan Poizner: Next one is from Linda. And Linda's from Washington, D. C. Linda writes, Hello, Susan. Congratulations on your new book. That's very nice. Thank you, Linda. Grow Fruit Trees Fast. My new book. So Linda writes, I think any zone information is very important for growing any plant. Good topic today. Okay. So for Linda, this is not a system we throw away.

It gives us some broad strokes, helps us figure out. it gives us a starting point.

We've got an email from Anne. Anne writes, Hello, Susan. Good topic today. The zone topic is very important. Hello to your guests listening to you from Ottawa, Ontario. Thank you, Anne.

And here we've got a question from Michelle. What role does a plant's origin, place of propagation, have on its ability to survive? Epigenetics is a fascinating science with regards humans. Does this also apply to plants?

Dan McKenney: Definitely. Yes.

[00:12:11] Epigenetics and Plant Adaptation

Dan McKenney: I'm going to let John answer that one because this is something that we have talked a lot about in other aspects of our work, and it absolutely is a fascinating subject.

John Pedlar: Yeah, it is. And I'm by no means an expert in it, but I can give my two cents for sure. The origin of where a plant originates from, is important in a few ways. First of all, we find that plants tend to be adapted to their local conditions. So that's going to dictate how well a plant is going to grow where it's planted.

And then on top of that, and this is more in in terms of wild populations but I'm sure it applies to garden populations as well, there's recently been insights that the temperatures that the tree seeds develop at, while still in the maternal cones, that actually impacts the preferred temperature of the seeds that are developed.

For example, if you've got seeds that are developing throughout the summer, in a really hot summer, even though there may be not in a particularly warm location, but it's a particularly hot summer, those seeds have shown evidence of being able to grow under warmer conditions. And that's what they call the epigenetic effect.

It's where the environment is actually determining the characteristics of the offspring.

Susan Poizner: So Michelle, I know because I know Michelle, is from Nova Scotia. And I find that a really interesting question because we have talked so much about the origin of a plant in terms of, it came from China a thousand years ago. We always keep that in mind, but this idea that where the seed is started, even if it's thousands of miles away from where that plant evolved, that that itself could make a difference.

And I know Michelle has a fruit tree nursery.

Maple Grove in Nova Scotia.

Excellent nursery. And they sell rootstocks to people who graft fruit trees. So often, people who graft fruit trees in Canada have to import rootstocks from elsewhere.

What a great question.

Is it your research or you've been reading research about it? Tell me a little bit, John, about your specialty. It is related?

John Pedlar: Yeah, it's more on the forestry side, but we've done a fair bit of research looking at that question of how, like how moving seeds around might help to adapt to climate change. So for example, if you gather seeds from a southern population, which is adapted to growing under warmer conditions, and say, move those northward, where we're anticipating that the climate is going to be warming up in the next few decades, then is that going to help to initiate populations that are pre adapted to the kind of climate that we're expecting at that location.

Susan Poizner: Amazing. Amazing. Okay. Let's have a look. Couple more emails.

We've got Dan writing from Allendale, Michigan, and Dan says, I am amazed at the U. S. fixation on our simple definition of plant hardiness zone. It's easy, but it doesn't satisfy the needs of a plant. I look forward to your conversation. Saying basically, yeah, it's got its limitations.

Okay, we've talked about the U. S. system, which has one factor, and we've talked about the Canadian system, where, which has seven factors. Somebody in the 60s did lots of research and they hand drew a map.

Okay, so now we can find out what climate zone we are in by looking at a climate zone map, whether we're in Canada or in the United States. So now, when you buy plants, is it pretty obvious, like on the label of the plant, that what zone that they are appropriate for? Do you find that it's been well publicized?

Dan McKenney: Yeah, I think so. Despite what I said at the beginning, I'm not trying to slag off on the hardiness zones. They are something that have worked in many cases for many years. They do have limitations, as your listeners have identified.

I believe that most plants also come with the experience of local gardeners and nurseries that sell them.

I think most nurseries are not going to sell things that are not suited to their area. In fact, I know of stories, even from my own location, that people did not want to sell them horse chestnut trees, for example, because they're not considered to be suited to the zone here in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

But, I also know, given that we're both foresters, that there are some horse chestnut trees that have been brought by people. And they grow here and they've done very well here. There's some large trees. So people push the envelope. I think that, over time, experience has really helped to calibrate the recommendations of what plants are suited for your particular area.

I just wanted to also mention here, Susan, that another sort of more modern approach that we have on our website is basically the climatic signature for many thousands of individual species, not just trees, but also perennials, grasses, things that gardeners are interested in, not just, let's say, professional foresters or ecologists.

So we can do this, and these maps on our website cover both Canada and the United States.

All we've needed to do is gather information about what grows at a series of locations. So we get data from like the Nature Conservancy in the U. S. Forest Service, Conservation Data Centers in Canada. We have a location of latitude and longitude, and we have spatial climate models. And basically that provides a signature of what climate those plants are suited to, and then we map those things.

So it's an individualized or customized map for the climatic range of literally thousands of species. And on the website, we have maps that we call "maps for gardeners" because they don't include precipitation, just temperature, because of the idea that gardeners can add water. But of course, in nature and more wild settings, you got to rely on what happens from the precipitation regimes there.

So, there are two kinds of maps there that give people insights about what would be suited to their area.

Susan Poizner: So let's share. What is that? How can people find the website, especially Canadians and Americans who want to maybe order something from over the border? They want to know what their climate zone is more precisely.

How can people find that page on the website with maps and that information?

Dan McKenney: So the website that I'm referring to is just planthardiness.gc.ca, but it does cover the United States. We don't have the USDA hardiness zones on there. We have our own version of covering Canada because we don't want to step onto the toes of the professionals down south.

But you can look at the standardized map. But you can also look for maps for individual species, and I think right now we've got, I don't know, 500 individual species. You can try to look them up by a common name or a scientific name. Common names, I'll just add, is a little bit tricky because a common name in western Canada might be a little different than a common name in eastern Canada.

But we've tried to put a lot of effort into identifying a broad set of what might be common names. So let's call it a rabbit hole of opportunities to look at what might be able to be grown where.

Susan Poizner: Okay, we have one more question. This is a question from William. Susan, do your guests have books published?

John Pedlar: I don't think we have books, per se. We have lots of

Dan McKenney: Articles.

John Pedlar: Yeah, we tend to, as research scientists, the scientific articles that we focus on, mostly.

We have certainly a number of publications in this area.

I wonder what the best way to.

Dan McKenney: Yeah, we've given out our data, and we've given out PowerPoint presentations to master gardeners in Canada and local naturalists. Sometimes we've had naturalist clubs or horticulture clubs who find out about this work, ask for a poster, and we just help them talk about the work and also the opportunity to contribute to what grows in their location. They have groups that can go around and I do basically an inventory of their community, which is fantastic for us because it's real. It's real citizen science in action.

Susan Poizner: I'll tell you what.

Oh, something I was thinking is, you can send me some links to any of the PowerPoints and I will put them so when people listen to the podcast, they can click on the links.

John Pedlar: And in the meantime, the website that Dan mentioned would also have those publications.

Susan Poizner: Oh, perfect.

Okay.

[00:22:12] Updating the Plant Hardiness Zone Maps

Susan Poizner: Dan and John, you guys worked together to update the climate zone map. That was not even your job and you did it. So I really want to talk about that.

Plant Hardiness Zone Maps, Dan and John, you guys took it upon yourselves to start having a look at Canada's Plant Hardiness Zone Map and to update it. How did that all come about?

Dan McKenney: It's a bit of a story about something that took on a life of its own. Back when I started working, I did my PhD in Australia and I did it in a place called the Center for Resource and Environmental Studies at the Australian National University, which was made up of some interesting people.

One of whom, did a lot of mathematical modeling. This guy actually had a PhD in pure mathematics. His name was Michael Hutchinson, and he worked with ecologists and agriculturalists. And one of the problems is maps of climate. Maps of past weather. There's only a limited number of weather stations.

But people need to know what's the weather like, or what has the climate been like in a place where there isn't a weather station, if you want to understand the role of climate in the distribution or abundance or productivity of plants and animals. In fact, so this guy, Mike Hutchinson, developed these methods using pretty complex math, something called thin plate smoothing splines.

Actually, somebody from Wisconsin, a quite famous mathematician named Grace Wahba, developed these methods. Anyway, Mike Hutchinson developed this tool called ANUSPLIN, which stands for Australian National University Spline Models, and when they first applied it, they actually used it to look into elapid snake distribution.

As many people may know, snakes are pretty prevalent in Australia, and they wanted to know, what's the role of climate in them?

And it actually helps to identify places in the landscape where particular species may occur. The short story is, I did my PhD there, I had the opportunity to continue to work with them. We didn't have maps for Canada of climate like they had there and I was able to bring that technology over.

And what actually was the epiphany moment was one time I was out in my backyard with my young son and I saw a seed packet and I said, Hey, we can do this. We can make maps of climate in Canada and one of the applications is hardiness zones. We can update the hardiness zones for Canada and other things, and we've continued to do that and we supply climate data and work with Environment Canada, who are the weather people in Canada, to actually distribute climate maps and climate data for all kinds of problems from looking at the waterfowl distributions, to tree growth, agricultural crop risks, all kinds of things.

But this one is, of course, one of our most fun applications, plant hardiness zones.

Susan Poizner: And John, what role, you play a different role. What role did you play in the updates?

John Pedlar: I was involved more on the technical side of the updates, as well as writing up the work and analyzing the work as well. I think that was about the main part, wasn't it, Dan?

Dan McKenney: Yeah, John's always a bit too modest. He's very much a full partner in this effort and provides a lot of the ecological interpretations and John's a great writer as well, so we've been a team for quite a few years now, perhaps longer than he may want. But, we've had lots of fun on the way doing lots of different things that are applications, including something you alluded to in the first half of the show about genetics.

We do a lot of work on genetics and understanding what the migration of trees and, how, because of climate change, we might want to assist in migration of trees.

[00:26:27] Climate Change and Plant Hardiness

Susan Poizner: So let's talk now about climate change. So here you guys are updating the system for Canada, the plant hardiness maps. Is climate change one of your considerations when you're doing those updates?

John Pedlar: Yeah, that's certainly one of the reasons why we undertook the updates. There's been two updates that we've done then. One in 2000 and one in 2014. The one in 2014, we're really able to focus in on the change over time, because we were able to compare that update in 2014 right back to the original map, which was about a 50 year period. And we were able to say so how much have these zones actually shifted over that 50 year period.

Susan Poizner: And had they shifted significantly, or are we just being overdramatic?

John Pedlar: They've definitely shifted.

I guess the answer is that it depends on what part of the country you're in. In western Canada, there've been much more drastic shifts in hardiness zones, upwards of three zone changes, so like from a 2 to a 5 kind of thing in some areas, not across the whole west or anything.

But in the east, it's been much more muted. I'd say about a shift of 1 zone on average, and even some areas where it's gone in the opposite direction. The zone has shifted to a more cold zone as opposed to a hotter zone.

Susan Poizner: Wow. Okay. We have an email here, from, let's see who it's from, James. Hi, Susan. Excellent show today. Lots of information. Loving it. From Toronto, Ontario. Thank you, James. And also I wanted to read on what you guys were talking about, in terms of how much is the climate changing, how much of it is climate change, how much of it is hardiness zones. There was a whole conversation on Facebook and I've got a few comments here I want to read.

Patrick from southern Germany writes, for us, it's not a shift in hardiness zones, but an increase in variability and extremes. That's challenging. Does that resonate?

Dan McKenney: For sure. That resonates. That's very important. So something that people need to keep in mind is that the zones are basically an average.

And as John indicated, they're based on 30 year averages, but of course 30 years are made up of 30 individual years. And one of the papers that we did, we compared the U.S. zones to the Canadian zones, and we looked at the variation through time that occurred with the U. S. zones. We haven't done that yet for Canada.

We hope to do that. It's as if you apply that same formula for each individual year. But, the the variation actually was more extreme, or more variable, in Western Canada than it was in Eastern Canada, which is interesting. But it's also consistent with what climate scientists look at and study. People from Environment Canada, who really dive deep into the statistics at weather stations where they've got really high quality observations over long periods of time.

There appears to be greater variation now and that's going to cause some problems. I know I've had some plants of myself that have not survived. One of the early stories here when we started doing this stuff was somebody was successfully growing a peach tree here in Sault Ste. Marie, which is pretty remarkable, and it grew to bear fruit, but then it actually died. So unfortunate, but a reflection of the variation that we get and in the various variables that drive the survival of those plants.

Susan Poizner: That makes sense. A couple more interesting comments here. We've got Rick from Northern Indiana.

Rick writes, last two years, we lost 75 to 85 percent of fruit tree crops due to mid-May hard freezes. We grow apples, plums, apricots, pears, pawpaws, and cherries. That is heartbreaking.

Here's another one. Dave from southern California. Dave writes, we're experiencing a shift in hardiness zones, as well as unpredictable weather patterns here in Southern California.

The entire month of January and early February were more like spring temperatures. Then, we had a hard freeze in April. Rainfall patterns are also changing. In 2019-2020, we had double our normal rainfall. In 2021-2022, we've had about half of our normal rainfall.

Is that typical for a more western state or province? That kind of extreme?

John Pedlar: Yeah, we've certainly heard about extremes in the Canadian western provinces as well. Yeah. I think that is the kind of thing that we're seeing. It's a real challenge to deal with those kinds of conditions as well. I think people are starting to get fairly aware of these drastic changes and extremes, but I think when we were new to this climate change game, we were probably thinking, things are going to warm.

Okay, we can probably roll with those punches. We'll plant varieties that are more suited to further southern locations, and we can change as needed.

[00:32:27] Adapting to Climate Change: Challenges and Variations

John Pedlar: But these changes and extremes have really thrown in a wrench into trying to be able to adapt to climate change.

Dan McKenney: I think it's.

Susan Poizner: Sorry. Go ahead.

Dan McKenney: I was just gonna say, it's not like a smooth path to a warmer planet. There's noise. Things go up and down. There's variation. This polar vortex that here we live with, in Ontario and Indiana, experience there, I think is disrupting the kinds of climate that, we were used to, right? And so, the variation is challenging for plants.

[00:33:09] Late Spring Frosts and Plant Sensitivity

Dan McKenney: So one of the things that we looked at, John in particular, was things like late spring frost and false spring. So yes, we get a period of time where it looks like it's going to be a nice warm spring, but then suddenly you get hit with a frost.

And if plants have already started their march into spring and summer with bud burst, they're going to have very sensitive tissue and it can cause big disasters. And that's happened at large scales. There are several documentations of that happening in the wild, not just for, let's say, gardeners.

[00:33:47] Listener Insights: Climate Change in Northern Indiana

Susan Poizner: Yeah, so, here we got another comment from Northern Indiana, so it's interesting. But this one has a bit of a hopeful twist to it. So this is what Bill writes from Northern Indiana.

I'm in Northern Indiana and have lived in the same region for all of my 60 years. The biggest change is our coldest month used to be January and now it's February. Then it warms up in March. Then we get severe cold spells and hard frosts mid May that kill the flush of new growth. Then, of course, the tree has to recover from that drastic loss of primary foliage from the little branches that grew, and then froze. And Bill says, and that makes the tree weaker and more vulnerable to pathogens and pests.

But here's what Bill says that I think is interesting. He says, I've been looking for later blooming nut and fruit trees to compensate. I'm also growing more cold tolerant plants like fruiting quince. They can survive down to 24 degrees Fahrenheit with blooms and a flush of new growth out in the spring when these cold snaps occur.

I think what Bill is saying is that with the fruiting quince, the blossoms and the new branches are just not as vulnerable.

Dan McKenney: Absolutely.

John Pedlar: Yeah. Yeah. And I think, that's a really good point that he makes there, that I do think that there's no magic silver bullet here to fix this problem, but certainly trying to diversify as much as possible is one thing that can be done to try to help at least minimize or spread around the impact so that you're not looking at a total loss in any given year.

Dan McKenney: One of the things that we look at with forestries in the kinds of genetics trials that john mentioned a little earlier, is the response not just to growth, but to bud break. So you may get a tree that grows a little slower because it has a later bud burst, versus one that you're trying to maybe maximize the growth for, but it might be a little bit more vulnerable for a period of time.

There are these trade offs, and much depends on the sort of scale of a gardener versus a commercial grower of any plant that may be out there. So there are those important trade offs that people have to think about.

[00:36:27] Strategies for Home Growers

Susan Poizner: I think that's the unique role that home growers can play, or small scale growers, because if I am growing fruit professionally, and I'm selling it in the supermarkets, or selling it from farmers markets, I don't want to take too many chances.

But home growers are the ones that can experiment, that can push the envelope a little bit, that can be creative. And I certainly know that there are a lot of fruit tree growers who have tried fantastic ways to protect their trees. For instance, in Ben Nobleman Park Community Orchard last year, our apricot trees were in full bloom.

And then there was a night Of frost predicted. So we all got together, and we linked up our tarps. We tied them together. And as a group, we put these tarps on sticks and we draped our apricot trees with these tarps to keep them that little bit warmer over the frosty night.

And then we took it off a few days later, once the frost had passed, and we had tons of fruit on the tree that year. So there is a unique role that home growers can play. There's no way a commercial grower could do that to 10, 000 apricot trees. It just would not be possible.

Dan McKenney: Yeah. Yeah.

Susan Poizner: Okay. We have an email here from Eric. Hello, Susan and guests. Eric wants a reminder. The website that you're promoting with more information, could you remind us what that website is?

Dan McKenney: Just planthardiness.gc.ca. If you type that into Google, it should come up.

Susan Poizner: Google will help us with that. planthardiness.gc.ca. fantastic.

[00:38:15] Sugar Bush Experiences and Climate Variability

Susan Poizner: Now, John, you have an interesting perspective as well. Can you tell me a little bit about that and have you experienced challenges in terms of climate change and hardiness with your sugar bush?

John Pedlar: Yeah, sure. I do have a sugar bush. Now, it's one that we've had for five years now. I'm just getting familiar with it. It has been used as a commercial sugar bush in the past, but right now, the lines were needing replacement, so that hasn't been done yet. So I've been just using it as a hobby sugar bush, and I've got 50 buckets on good old fashioned taps. That plus a lot of hard work gets you a little bit of maple syrup at the end of the season. But I guess one thing I've been struck by out in the sugar bush, where you do spend a lot of time thinking about climate and weather, is just how variable it's been over the last five years.

We've had early seasons, late seasons, short seasons, long seasons, good sap flow years, poor sap flow years. So I'm just trying to get my head wrapped around that, the amount of annual variability there is in that, and I'm not able to, at this point, say if all of that is climate change or if any of that is climate change. But it's all been fun and it's all been a good learning experience for sure.

Now, I have done a bit of looking into climate change impacts on sap, kind of publications in the literature, and there's not that many studies out there that have looked at it. But generally, they point to the fact that, not surprisingly, the season for sap flow is moving forward in the calendar, so it's happening a bit earlier, and it's ending a bit earlier.

And it does appear that the sugar, levels in the sap might decline a little bit with these increasing temperatures. So, people have pulled that together to make some projections for the coming century, and it does look like they're projecting around a month. Sap flow dates moving forward about a month in the calendar, with some reductions in syrup production. But it's not the all-out disaster that is predicted for some crops out there.

Certainly in Canada, it would suggest that there's still going to be maple syrup being made for the next foreseeable decades, anyway.

Susan Poizner: Hey, we're Canadians. We can't do without our maple syrup. I'm sorry. That's just not an option. Okay. I'd love to wrap up with both of you.

[00:41:04] Advice for Gardeners Adapting to Climate Change

Susan Poizner: Do you have any advice for listeners who are listening to this?

Thinking of buying new plants, thinking of climate change, thinking of climate zone maps or hardiness zone maps. What advice or recommendations would you have for us moving ahead as we adapt our gardens to a new world? Whatever that's going to look like?

Dan McKenney: John, do you want to go first, or me?

John Pedlar: Well, advice is tough in this world.

I do think that, as you mentioned, Susan, it's a different situation for hobby gardeners versus large scale operations. You can take a lot more risks and almost have fun with it as a hobby gardener. Try pushing the envelope. But not so much in the large scale operation. I think you still need to exercise some caution as far as what varieties you're going to try.

Dan McKenney: I think, yes, smaller landowners, people who want to experiment. It can be a fun thing and talk to your nursery. They have experience and should have experience because they talk to many people, so they will have a sense of the degree to which particular plants seem to be suited for their area or not.

I want to say too, is that, for those listeners that may be interested, there are opportunities to contribute to something like a citizen science project.

You can push the envelope. See what happens. When we take data, we ask people that only contribute observations of things that have grown for at least five years. These are meant to be looking at the long term average conditions and also things that survive more than one or two seasons, one or two years.

In the coming decades, there is going to be more variation. There are going to be hard frost, early springs. It's not going to be a smooth path to a warmer world. It's very variable across the country and across the continent. As we know, western US, western Canada, some tremendous droughts that are going on now. There's heat domes last year that cause fires.

So it's going to be something that we're all going to, I think, experience a little bit differently through time, but trees are definitely a great thing to be planting, especially fruit trees. Right, Susan?

So let's all do our bit. Trees suck up carbon dioxide, and that helps. Definitely, that helps.

Yeah, I'd say go ahead and and keep planting, folks.

Susan Poizner: Oh, that is so nice. And so inspiring.

[00:43:37] Closing Remarks

Susan Poizner: And thank you to everybody who participated in the show today with your comments, with your questions. This show is so much better because of your participation. It's just wonderful to get people's perspectives and point of view. And thank you so much to my two wonderful guests today for coming on the show.

And also, I want to say we appreciate you and the work you did with the plant hardiness zones here in Canada. Nobody forced you to do it and you guys took it upon yourselves. Thank you.

Dan McKenney: Thank you very much, Susan. Yeah, we're hoping to do another update within the next year, so stay tuned. Thanks for this opportunity.

Susan Poizner: Okay. And maybe give a little poke to your colleagues in the United States. I don't know if they're doing updates. We'll have to get them on the show to talk about it. Maybe they'll maybe now they will, because they know they're competing with you. That's the thing. thank you so much for coming on the show today.

And, hopefully you will come back again someday and give us the next update. So thank you for joining me today.

Dan McKenney: Sounds good. Thank you, Susan.

Susan Poizner: Okay, that's it for the show today. I can't believe another hour has come and gone. If you missed the beginning of the show or you want to listen to the whole show again, you can go to orchardpeople.com/podcasts.

And that's where I put all the recordings. You download your podcast. You can listen to previous episodes and learn all sorts of great stuff and meet other wonderful guests from the show.

Also, if you want to read articles about fruit tree care, you can go to orchardpeople.

com and I have articles, ebooks, and a lot more.

Finally, I launched my new book as well. And if you want to grab a copy of Grow Fruit Trees Fast, you can go to https://orchardpeople.com/growfruit-updates/. And I would love it if you read the book. And, I would love to hear your feedback on it as well. So that's all for the show today.

I hope you guys will join me again next month when we are going to dig into another great topic. So I'll see you then. Bye for now.

Creators and Guests